Steve Mumford | Painter

Many artists suffer for their art, but few actually risk life and limb. Since 2003, SVA alumnus Steve Mumford (MFA 1994 Fine Arts) has made several trips to Iraq and Afghanistan to capture the war-torn regions through his paintings and drawings. The August issue of Harper’s Magazine features a dozen of Mumford’s paintings, which were created during his time embedded with the 3/6 U.S. Marines in Marjah, Helmand Province, in 2010 and with the 2/3 Marines in Nawa, Helmand Province, in 2011. Mumford recently spoke to the Briefs via email about the risks and rewards of his work.

How did you become a combat artist? What attracted you?

First I would say that I don’t call myself a combat artist; I’m an artist who drew in Iraq and Afghanistan as part of my process. I spend half of my time painting in oils in my studio in NYC. Harper’s Magazine has sent me to draw the BP oil spill in Louisiana, so I’m interested in engaging current events with my art.

Of course, a war has singular challenges. The topic attracted me in part because war is an intrinsically dramatic narrative.

Can you describe your process, and what it’s like to paint or draw alongside troops on the battlefield? Are you able to relax (or lose yourself) in the same way that you might while working in your studio?

Good question. Drawing publicly is never like being in the studio—you’re often working with an audience, which I find challenging. You usually don’t have time to beat around the bush. If the drawing starts to “click” then your self-consciousness drops away.

How dangerous has it gotten for you?

Occasionally very. I’ve been near IEDs (Improvised Explosive Devices), had multiple RPGs (Rocket-Propelled Grenades) hit the vehicle I was in, and been shot at on several occasions. I’ve been very lucky.

What has surprised you most?

Probably how easy it is to fall into the role. The soldiers accept you as just another media type; Iraqis and Afghans already find Westerners odd, but at least this practice is comprehensible and out in the open.

How do the soldiers (or any of your subjects) typically feel about being painted? Do they mind you being there?

Not usually, so long as you can keep up and don’t cause any problems. When I was embedded at the Baghdad ER, a mass casualty event occurred. A Senior Officer entered the crowded room and announced, “All non-essential personnel should leave the room now!” I decided that I was essential, and I stayed, drawing. No one asked me to leave after that. If you enter a war zone to do art, you should adopt this point of view.

You recently had a show at the CMCA in Rockport, Maine, which generated some controversy. One reviewer questioned your objectivity and called your work “propaganda.” How would you respond to that?

This point was a bit silly, as it was based on a misunderstanding: I’ve never claimed to be objective and don’t think objectivity is good for art. I set out to be subjective. I’ve admired many of the soldiers I’ve met and never tried to hide that in my work. Likewise for many Iraqis I drew. I don’t think this ever stopped me from being honest in my drawings. The viewer has to use their own smell test to determine if someone’s account of a war zone feels true, or if they’ve somehow been played.

I would also add that it can be surprisingly difficult to find the actual combat, let alone carnage, which tends to get cleaned up quickly. In battle, someone can be shot a block away and you’ll never see it unless you happened to be right there.

I sometimes hear the line from the left that an embedded reporter has been compromised. From my experience this reasoning is not just false, but lazy—do they ever read the papers? The reporters I met on embedments were very sharp and skeptical, and their reporting in the major news outlets demonstrates this all the time.

All that said, I was very flattered to have people waving pickets outside my show!

The paintings from Afghanistan in the recent Harper’s were inspired by Winslow Homer’s Civil War studies. Was Homer the best at this? Are there other combat artists that inspire you?

It’s hard to say if he was the best, but he certainly was a great artist, and the greatest inspiration to me. His paintings about the war done after returning from the front are of even greater significance. There were probably two dozen combat artists crawling around the Civil War theater at any one time, working for Harper’s Weekly and Leslie’s Illustrated.

Frederick Remington is another wonderful artist, he covered the Spanish American War and then the Frontier Wars out west. He tried mightily to break down the perceived difference between fine art and illustration. I think he succeeded.

Of course Delacroix, David and Gericault are other inspirations for me. And most of Baroque painting!

What do you hope to achieve or convey through your combat paintings?

I hope the quick sketches succeed in putting the viewer in the shoes of the people depicted. And in my larger paintings I’m trying to get at the deeper issues around war, of beauty, drama, fear and camaraderie. I try to get viewers to understand that it’s not adequate to simply say, war is bad, or, war is a crime. War and peoples’ motivations around it are complex and contradictory, like human nature itself.

To view more of Steve Mumford’s work, visit Postmasters Gallery.

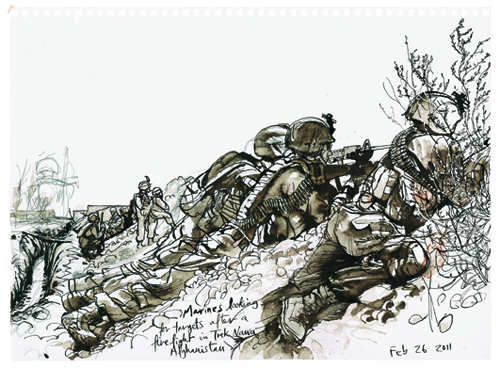

Images: (first) Marines wait while an explosives and ordnance team defuses a bomb buried one hundred yards away. Marja, Afghanistan, 2010. (second) Marines looking for targets after a firefight. Trek Nawa, Afghanistan, 2011. Images by Steve Mumford courtesy of Harper’s Magazine.