Winnie Owens-Hart | Ceramic Artist

Passing On An Ancient Tradition

Winnie Owens-Hart ’71 (Crafts) came of age in Virginia, the child of government employees who stressed education above all else. Even at age 5, the future academic would get lost in the pages of her encyclopedia. “I always looked at ‘A’ first, for obvious reasons, particularly the section on ‘Africa,’” she says.

Winnie Owens-Hart ’71 (Crafts) came of age in Virginia, the child of government employees who stressed education above all else. Even at age 5, the future academic would get lost in the pages of her encyclopedia. “I always looked at ‘A’ first, for obvious reasons, particularly the section on ‘Africa,’” she says.

“I had a fascination with clay and vessels, and what I distinctly remember is a picture of a granary that I just saw as this huge pot,” says Owens-Hart, a Howard University professor whose work today focuses on entrepreneurial support of traditional ceramics.

In her childhood home, copies of Jet, Ebony and Time were essential household reading. One issue of Time, with a black Adam and Eve on its cover, spurred dinnertime discussion of Africa as “the cradle of civilization.” “From that point on, if I saw somebody who looked like me, I figured they were from the homeland and I needed to talk to them. I decided that someday I needed to go to Africa.”

Owens-Hart arrived in Philadelphia in the late 1960s, embarking on a study of subjects as wide-ranging as ceramics and city planning. It was in those ceramics classes with their emphasis on pottery from China and Japan, or Wedgwood from England that Owens-Hart first posed a new question. “I used to say, ‘What about African ceramics? If the oldest known humans are from Africa, they must have been making pots,” she said. “They had to eat, they had to cook, they had to store food. I knew there had to be ceramics there.”

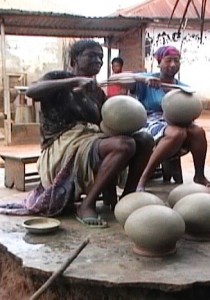

While a student at the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of the Arts), Owens-Hart unearthed a film made by German ethnographers that depicted the African pottery techniques she’d wondered about. On film, she witnessed traditional women using methods that she never saw in Western pottery, such as the use of clays with dissimilar moisture contents to build the separate parts of a single pot. The film confirmed her belief in the importance and existence of African pottery.

She would see the techniques in person in 1977, when she was selected to travel to Lagos, then the capital of Nigeria, for Festac, a festival highlighting artists of the African diaspora. She returned the following summer to study via a National Endowment Craftsmen Fellowship, subsequently taking a teaching position with the Federal Government of Nigeria at the University of Ife in Ile Ife, Nigeria. Soon after, she studied traditional pottery in Ipetumodu, a village near the university.

On one of those trips, she was riding with friends in a VW bug en route to Northern Nigeria. “We drove past a rural compound and the gates were open and through the opening I saw that huge pot.”

It was a granary – a pot just like the one from the pages of her childhood encyclopedia. Owens-Hart yelled for the driver to stop and bolted from the car, camera in hand, darting – unwisely – inside the private compound. “I was in my impulsive 20s,” she notes. “God looks over babies and fools.”

Those early trips to Africa informed a lifetime of teaching, most of it at Howard, where she began lecturing in 1976. Owens-Hart would return to Ile Ife three decades later to conduct workshops in the process of off-the-wheel pottery techniques.

This fall, Owens-Hart will return to Philadelphia to present her own documentary film, “The Traditional Potters of Ghana: The Women of Kuli,” along with a short as part of workshop series, “Pots in America: The Transcontinental Passing of an Ancient Tradition,” led by the Fleisher Art Memorial.

Owen-Hart’s work will no doubt inspire a new generation of eager young people to begin dreaming of Africa.